Delving into Biodesign (aka Human-Centered Design) at Edwards Lifesciences

A newly popular framework for insight-driven iterative innovation, called the Biodesign Innovation Process, is focused on life sciences innovation and has been honed at Stanford over the last two decades. We are fortunate to have two of the leading Biodesign experts in SoCal working together at OC-based Edwards Lifesciences. Todd Brinton, MD, currently the Chief Scientific Officer at Edwards with more than a dozen years as a key leader at Stanford Byers Center for Biodesign; and Farzad Azimpour, MD, SVP Strategic Innovation at Edwards with almost nine years at Stanford Byers Center for Biodesign, are subject matter experts extraordinaire and cardiologists. With such expertise available, the Alliance convened a group of 15 SoCal innovation leaders to spend a few hours touring Edwards’ innovation facilities and then delving into a discussion on the key elements of this powerful approach.

Our morning started with a fascinating tour of their amazing headquarters with the majority of our time spent in the glass observation area overlooking their heart valve manufacturing and assembly area. We learned about the key assembly steps and quality control methods for what is a surprising craft-driven approach with expert sewers working as tightly-knit teams to assemble these life-saving devices. With this as context, we retired to their training center where Farzad shared his knowledge and perspective on the Biodesign process. (I have selectively included several slides from his presentation.)

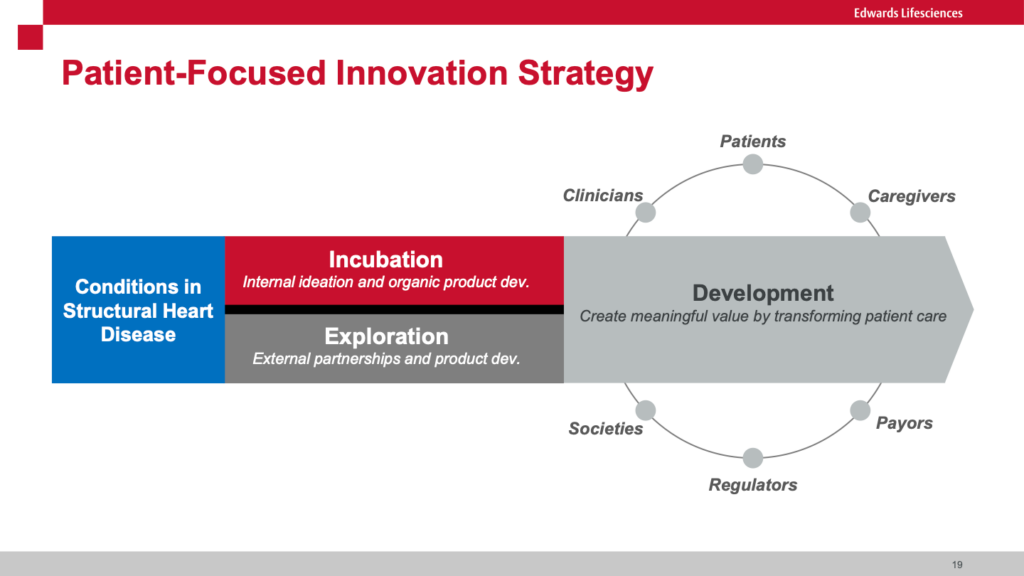

Farzad leads the incubation team that develops new breakthrough products internally while his colleague Virginia Giddings leads in parallel the Exploration team that focuses on third party solutions and partnerships. He explained that his work focuses on moonshot innovation rather than incremental development.

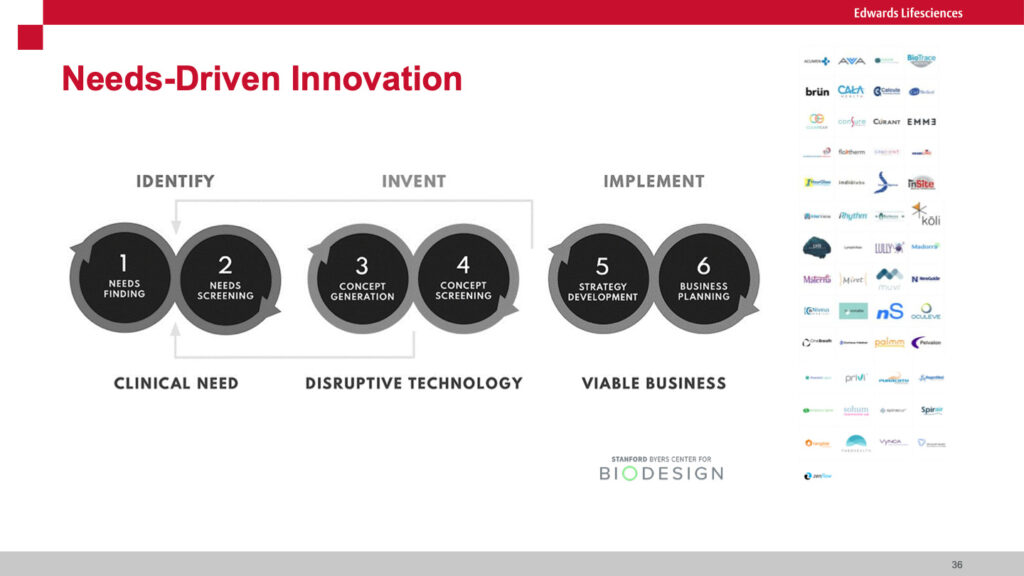

Farzad highlighted the difference between “push” innovation where new technology is brought to users vs “pull” where the user’s needs (primarily patients in the case of Edwards) drives the development of new technologies. He cited Josh Makower, MD (Co-founder of Stanford Biodesign) who stated “A well-characterized need is the DNA of a great project!” This well articulated need then becomes the “license to invent.” He highlighted the need to rigorously down-select from a large universe of unmet needs to those few that are “highly unmet.” He walked us through the process of developing a well articulated needs statement that includes the problem, the served population and the target outcome. When calibrated correctly, this statement serves as a North Star for designing a series of early stage and pivotal clinical trials. He shared the “Creative Abstract Exercise” where the potential innovation is described in a mock article as if it were going to be published in a prestigious journal. I have seen similar approaches using mock press releases. These techniques allow innovators to more vividly describe what success might look like.

Obviously such approaches avoid the “solutions seeking a problem” difficulty. One of our guests from a leading healthcare system mentioned they adopt a similar needs-driven approach but delve deeply into why the need has not been previously addressed to make sure there are no structural blockers. He mentioned they rigorously validate potential solutions to ensure they will effectively scale across the health system versus addressing more limited conditions. In his case, they are obviously concerned about the proliferation of approaches in a system that is trying to achieve some level of uniformity of outcome. He described the risk of “pilotitis” where clinical heads commit to testing numerous solutions in their unique domains.

Farzad shared how he and his teams implement into daily practice the 7 rules for brainstorming from global design and innovation firm IDEO (where he previously served as Director of Health):

Rule 1: Defer judgment

Rule 2: Encourage wild ideas

Rule 3: Build on the ideas of others

Rule 4: Stay focused on the topic

Rule 5: One conversation at a time

Rule 6: Be visual

Rule 7: Go for quantity

There was an extensive conversation about how Farzad deploys his competing team (each having 4 – 5 members with complementary skills: clinical, engineering and business) to develop breakthrough ideas, how they are filtered, and how they are developed into early proof of concepts. His teams have captive support resources, and when they need corporate support they are given the highest priority so as not to create delays in the innovation process. The final and best solutions are presented to Edwards’ executive leadership team to vie for funding into commercial product. In the almost four years of operations, two projects have made it into the commercial product development pipeline.

Another interesting program Farzad shared with the group was the Edwards Innovation Fellowship Program where early careercardiologists and cardiac surgeons can work full time for 12 – 24 months with his innovation team on this incubation effort. This opportunity benefits both the creative clinician and the innovation team by bringing in different perspectives and approaches.

Besides peppering Farzad with questions, the group shared some of their own innovation best practices. It was clear that understanding needs, brainstorming, down-selecting and rapidly iterating were shared elements across them all. It was a productive and collaborative day of learning and fellowship, and we were particularly grateful to Farzad and Edwards for sharing so generously with our innovation leadership group.

We are planning our next site visit early in the fall at JPL. It will be focused on ideating moonshot missions – and they for sure know about moonshot missions! If you are a senior innovation leader and might want to join us please reach out to Katie (katie at alliancesocal.org) to be considered.